|

| Sense of Style (Steven Pinker) |

Askew Arts Calendar

Monday, March 4, 2024

Why people can't write, according to Harvard psychologist

Monday, September 21, 2020

Mandy Kahn’s PEACE CLASS (free, 9/23)

FREE from The Philosophical Research Society

ABOUT

It’s time to talk about peace — not as the opposite of war but as a

universal power source that any individual can plug in to for free. Peace

is an energy that flows and can be used to build peace in

the individual experience and by extension in the collective

experience.

It is not the opposite of war: Peace is a state where war cannot exist. The nonexistence of war in the experience of peace is simply one small aspect; war is simply one of many things that cannot exist there.

To focus on what is not present in the state of peace is to fail to focus on what is present and how what’s present can be used. This distraction keeps us from understanding the nature of peace and from using it to build a world that is continuously peaceful — a world in which it is remembered that all plants and bodies of water are holy, a world in which all are perfectly free and, by way of that freedom, are themselves, who by way of such selfhood are creative.

That is available to us, and it’s available for free. The free energy source of peace cannot be bought or commodified. It can only remain free. And it can only be used in one way: to build a peaceful world — such a world as is our birthright.

Mandy Kahn is the author of two poetry collections. Her work is included in The Best American Poetry anthology series and she is the subject of the forthcoming documentary Peace Piece: The Immersive Poems of Mandy Kahn. Kahn presented a program of peace-building interactive poems at the Getty Museum in 2019; she hosts a live event series at the Philosophical Research Society called I LIKE PEACE.

Drop in for a class, or come for the full series. No need to attend the first meeting; drop in at any point. Eventbrite

TIPS:

- Chrome works best for this platform - if there are any delays in the connection please try using Chrome.

- When you enter the event you may be asked if livewebinar can access your microphone and camera. In order to participate in the event please select OK. You will have an option to turn off your audio and/or camera during the event at any time.

- Please have writing materials on hand.

Sunday, May 17, 2020

Writers' Secret to a Happy Marriage

|

| Anna Dostoyevskaya by Laura Callaghan from The Who, the What, and the When |

After his elder brother died, Dostoyevsky, already deeply in debt due to his gambling addiction, had taken upon himself the debts of his brother’s magazine. Creditors soon came knocking on his door, threatening to send him to debtors’ prison.

(A decade earlier, he had narrowly escaped the death penalty for reading banned books and was instead exiled, sentenced to four years at a Siberian labor camp — so the prospect of being imprisoned was unbearably terrifying to him).

As part of the deal, he would also have to produce a new novel of at least 175 pages by Nov. 13th of the following year. If he failed to meet the deadline, he would lose all rights to his work, which would be transferred to Stellovsky for perpetuity.

Only after signing the contract did Dostoyevsky find out that it was his publisher, a cunning exploiter who often took advantage of artists down on their luck, who had purchased the promissory notes of his brother’s debt for next to nothing, using two intermediaries to bully Dostoyevsky into paying the full amount.

His friends, concerned for his well-being, proposed a sort of crowdsourcing scheme — Dostoyevsky would come up with a plot, they would each write a portion of the story, and he would then only have to smooth over the final product.

But, a resolute idealist even at his lowest low, Dostoyevsky thought it dishonorable to put his name on someone else’s work and refused. There was only one thing to do — write the novel, and write it fast.

|

| Anna Dostoveskaya lived to be 71. |

Anna, 20, had taken up stenography shortly after graduating from high school hoping to become financially independent by her own labor. She was thrilled by the offer. After all, Dostoyevsky was her recently deceased father’s favorite author, and she had grown up reading his tales. The thought of not only meeting him but helping him with his work filled her with joy.

The following day, she presented herself at Dostoyevsky’s... More

Friday, May 15, 2020

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Submit for the Hillary Gravendyk Poetry Prizes

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sunday, April 26, 2020

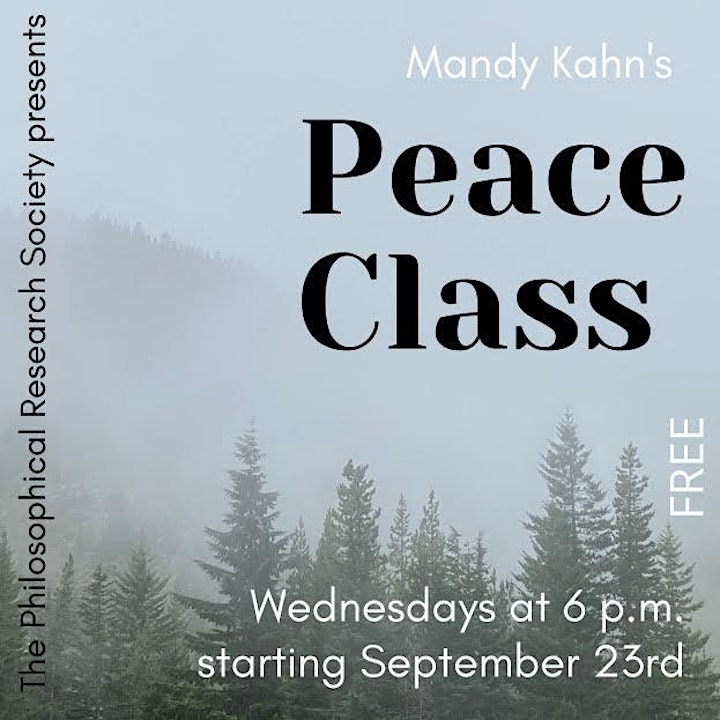

Who was the REAL "Shakespeare"?

Without an understanding of these blatant challenges, the most knowledgeable follower of “Shakespeare” is kept from the author and how he lived, essential to appreciating any work of art. The key that turns the lock opens the door.

Secrets of the Droeshout Portrait in Shakespeare’s First Folio

by WJ Ray

- Full essay with detailed illustrations and appendices: PDF

- VIDEO: "The Secret Evidence of Who Wrote the Shakespeare Canon" from Willits Community TV Inc. on Vimeo. More

It's Shakespeare's birthday today (April 26)

He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon" (or simply "the Bard") because he is from Stratford-on-Avon [5].

His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship.

- In fact, everything attributed to him is of uncertain origin. Whoever wrote it, it was almost certainly not this poorly educated bumpkin with no way to know the things covered in the plays and poems. The Earl of Oxford or a woman, as the evidence indicates, are the likely actual authors using the pseudonym "Shake-spear."

Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna and twins Hamnet and Judith.

At age 49 (around 1613), he appears to have retired to Stratford, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare's private life survive.

This has stimulated considerable speculation about such matters as his physical appearance, his sexuality, his religious beliefs, and whether the works attributed to him were written by others [8, 9, 10]. These things were definitely written by others. More